Most nonprofits acquire new donors at an up-front loss. In direct marketing terms, this loss is measured as “cost per donor.”

It’s an important value that represents an organization’s investment in new donors – what each new donor “costs.” Once acquired, the expectation is that the organization’s new donors will yield some return that exceeds the initial investment.

So what’s a “good” cost per donor? And what should your organization’s be?

Unfortunately I can’t tell you … because there’s no one answer. Acceptable cost per donor rates vary widely among organizations. And believe it or not, the lowest possible cost per donor isn’t even necessarily the best cost.

But you can determine your organization’s acceptable cost for new donors – by looking at your existing ones. Here are the things you need to consider:

How much do your donors give after you acquire them? There are many ways to examine this question, and donor lifetime value analysis can quickly become a complicated, caveat-riddled exercise. But one simple place to start is to isolate all the new donors your organization acquired in a single year, look at what it cost to acquire them and then look at how much subsequent net revenue they’ve generated.

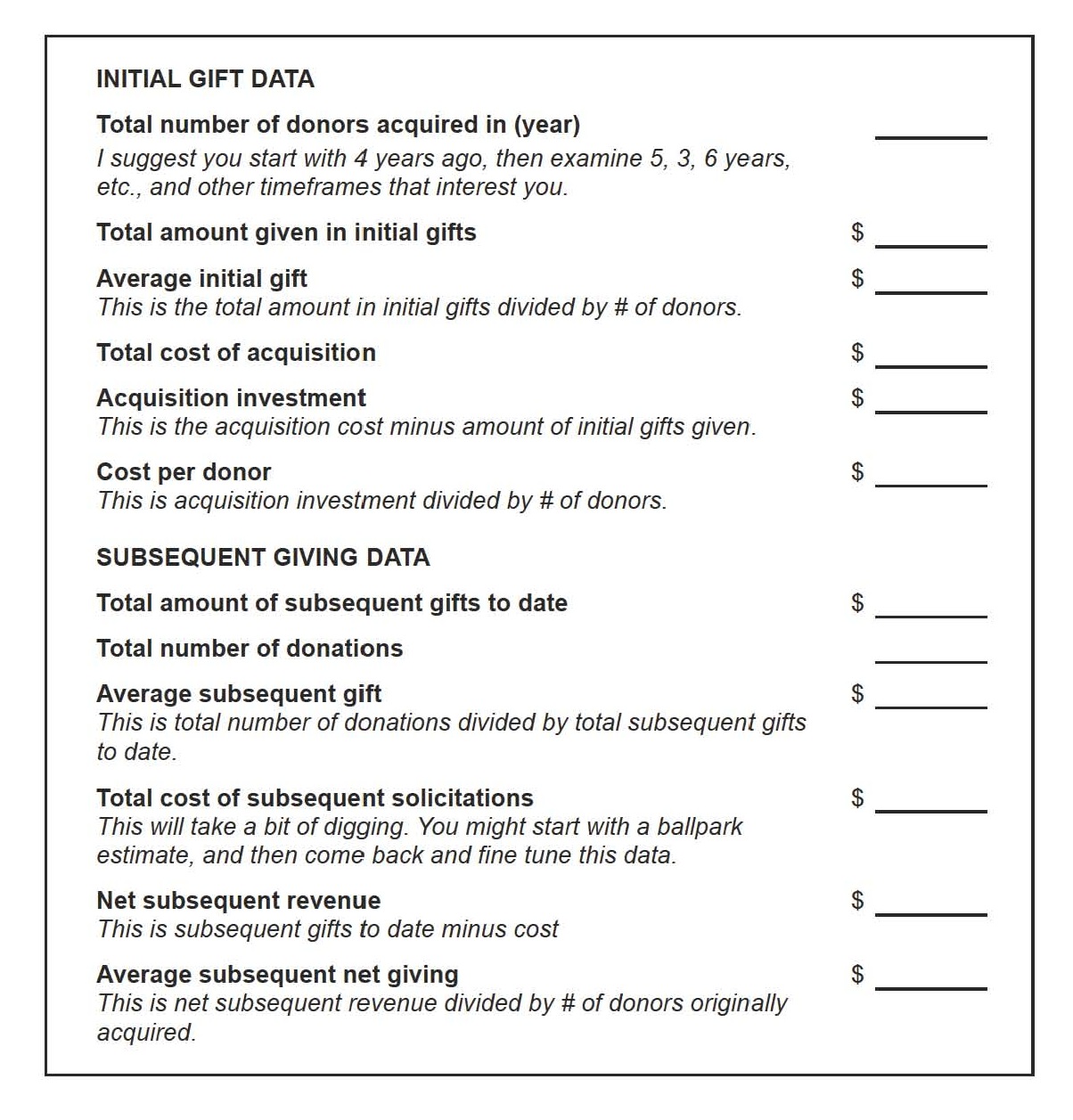

Here’s a checklist for the data you need to pull:

After you’ve pulled this data, step back and look at how much you spent per donor on acquisition, and how much you netted per donor subsequently. I’ll come back to interpreting your findings in a moment, but there are a few other things you also need to consider:

After you’ve pulled this data, step back and look at how much you spent per donor on acquisition, and how much you netted per donor subsequently. I’ll come back to interpreting your findings in a moment, but there are a few other things you also need to consider:

How many of your donors eventually turn into major donors, and how much do they give? Your organization may pull major donors out of its regular membership or donor development program, but don’t forget to include them in your evaluation. After all, if you spent money to acquire a donor that eventually turned into a major donor, then their giving as a major donor is an important element to consider when setting an appropriate cost per donor threshold.

How many new donors seem to appear out of no where, making a gift to your website or sending a check though you don’t recall asking them? It’s not all concrete cause-and-effect in direct marketing. The public awareness cultivated by your donor acquisition program, your organization’s presence in the public eye, and your organization’s programs themselves will all contribute in immeasurable ways to your new donor acquisition results.

When you tally new donors acquired and measure their post-acquisition performance, don’t only look at donors acquired through directly attributable sources. Also include your newly acquired “no source” donors in your analysis, because while it may appear as if you didn’t do any work to acquire them, or they were “free,” you actually did do something to acquire them; you just can’t trace it.

Remember how you calculated cost per donor earlier by dividing your total acquisition cost by total number of new donors? Don’t forget to include your “no source” donors in this equation. When you do, you’ll see that your real cost per donor is a little lower than you thought.

How long does it take you to recover your initial acquistion investment? Six months, twelve months, eighteen months, more? Again, I can’t tell you the “right” amount of time it should take your organization to recover its initial acquisition cost. But you can find out what your organization’s current cost recovery time is, and factor it into your determination of acceptable cost per donor. Your organization may, for example, be willing to carry a lower initial acquisition cost longer than a higher one.

How does donor value vary by source? After you’ve considered all of these things, you can dig deeper if you’d like and compare your initial cost per donor and subsequent value by source (for example names you acquire at an event compared to the names you acquire through a particular mailing list). This can be helpful because sometimes donors with a higher up front cost per donor turn out to be more valuable over the long term than donors with a lower initial cost per donor.

Now what? Now that you’ve examined all of these things, and maybe some other considerations that came up during your analysis as they often do, what do you think of your cost per donor?

If you like what you see, great! You can tell your Board with confidence that your cost per donor of $ (fill in the blank) is appropriate based on the revenue your donors are generating post acquisition.

On the other hand, if you don’t like your cost per donor relative to the subsequent revenue they produce, the good news is you can do something about it.

You can always work on lowering your up front cost per donor. But more importantly, there’s nothing like a cold hard look at cost per donor and subsequent revenue to really drive home your responsibility to actively engage your organization’s new donors immediately and often post acquisition.

If you acquire new donors at some cost and they only hear back from your organization once a year, you certainly won’t achieve your full fundraising potential. You may not even recover your initial cost per donor investment. But if you are in touch with your donors often, via multiple channels, and with varied messages that aren’t always strictly about fundraising, your organization will undoubtedly enjoy the support of donors that are more engaged, more generous, and much more worth the initial investment to acquire them.

So as you set out to define the right cost per donor for your organization, remember that the most important factor in determining donor value is you.

Editor’s Note 9/6/16: This article was originally posted in 2011, but is even more relevant today as increasing proportions of donors who are motivated by direct mail give online. Trace the origins of your new donors carefully and follow their tracks through both on- and offline universes after their initial gift. Not only will your detective work help you evaluate your organization’s true cost of new donor acquisition, but it will also give you insights on the relative roles of your fundraising and communications channels.

The saying “content is king” has long been a dictum of web design, referring to the importance of desirable, engaging information to a website’s success, as recently affirmed in this

The saying “content is king” has long been a dictum of web design, referring to the importance of desirable, engaging information to a website’s success, as recently affirmed in this  The simplest things can escape us sometimes. We get so involved in the details of inspiring people to make donations to our organizations that we forget about our donors themselves. We can tell you how our programs our doing. We can tell you our average gift, percent response, open rate, cost to raise a dollar, unsubscribe rate, net/M, and so on.

The simplest things can escape us sometimes. We get so involved in the details of inspiring people to make donations to our organizations that we forget about our donors themselves. We can tell you how our programs our doing. We can tell you our average gift, percent response, open rate, cost to raise a dollar, unsubscribe rate, net/M, and so on. In direct response fundraising, “membership” in an organization is often a symbolic donor status, but a highly effective means of articulating and cultivating donor relationships. A donor is someone who makes a gift, but a member is someone who belongs.

In direct response fundraising, “membership” in an organization is often a symbolic donor status, but a highly effective means of articulating and cultivating donor relationships. A donor is someone who makes a gift, but a member is someone who belongs.